Dear Designer,

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been going back and forth about buying a brand spanking new camera.

Yes, I have a late model iPhone with a decent camera. And I have a number of decade-old digital and film cameras sitting around, mostly collecting dust.

And I realize that the best camera is the one you actually use.

After a lot of research, I settled on what the kids are buying these days — the pocket-friendly, highly versatile, and good-looking Fujifilm X100VI.

And why not?

I have been shooting since I was 12 years old. I had a darkroom in parents’ basement when I was 15, developing my own black and white film and arty prints. In grad school, I taught photography to fine arts undergraduates for a a couple of years.

I loved teaching photography. I love photography. I have even loved photographers. I deeply appreciate photography in all of its complexity, nuance and silliness. I spent years studying the greats.

I have nearly 50,000 photographs in my library. And I shoot with my iPhone almost every day.

But something recently shifted for me. I have been trying to figure out how to write about this.

Photography, brilliant, brash, and bracing, has become a scourge on our planet and for our souls.

And I think it’s high time that we designers fundamentally reconsider its use. In fact, I believe we should stop using photographs in our work.

A manifesto against photography

Some 50 years ago, the philosopher Susan Sontag wrote a very important essay called “On Photography” where she presciently recognized the immense power that photographs were having on our culture, on capitalism, and on our capacity for compassion.

She tore the veil of the good times that photography tries to engender. Sontag wrote that photography and the machinery of photographic reproduction (including that silicon device in your pocket and those videos it turns out) turns all subjects into objects:

Like guns and cars, cameras are fantasy-machines whose use is addictive… there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.

This form of reification was not new. Feminist critical theory explored it concept for years. The male gaze, the raw objectification of women, the misconceived concretization of the world through ideology… these are old and well-worn tropes.

But today, we march towards new digital frontiers in which intelligence is made artificial, in which servers are spies, and in which truth is in turmoil.

If Dear Designer is a project of praxis — a public combination of design theory and practice — I offer the following points as a preliminary manifesto against photography.

We are saturated in photographs. There are 5.3 billion photos shot every day, globally. The vast majority of these images will never be looked at again. We are not swimming in images — we are sinking in them.

Storing photography is irresponsible. There are now 15 trillion digital images in existence. All of them are sitting on server farms, which use massive amounts of electricity to maintain, back up, and cool.

There is nothing new to shoot, except for people and events. Everything has been photographed a billion times. Documenting our every move for others creates more yearning, anxiety and restlessness.

Photography fuels a rapacious tourism. Social media has created fossil-fuelled global vacationing, leading to cities that can afford tourism but not human habitation. Venice is empty of people and full of visitors.

Photography lies. A photograph is always already a poor interpretation of the real. But we accept the opposite. With further advances in technology, it will be impossible to tell what is objectively true.

Photography is an extractive activity. A photograph takes our collective reality and makes it unchanging. It shrinks our time into discrete experiences without offering greater hope for a better future.

Cameras create vast waste. 1.4 billion phones (e.g. pocket cameras) are produced every year and 5.3 billion phones are disposed of. We cannot continue to make and export our e-waste indefinitely.

Photography is disrespectful and often grotesque. Pornography and violence on phones exploit our humanity. They take away our attention, our energy, and our courage to connect.

Photography stylizes poverty, race and kindness. While written language makes it hard to trivialize social challenges, photography makes issues paper thin, reinforcing our indifference and indecision.

Photography promotes globalized consumerism. Online commerce infatuates because every image is a substitute for the object. We buy needless objects because of the mass presentation of needful images.

Surveillance capitalism demands photographic acceptance. The cameras in our pockets are also tools for the mass monitoring our locations and behaviours by corporations and governments.

Photography offers undemanding communications. Photographs offer easy and fatuous production. With the rise of AI, we are left with mass-produced visual crumbs and impoverished imagery.

So what are we left with?

Without photography, what is left for designers? Can the graphic trifecta of text, image, and structure survive a world in which we reduce our dependence on photography for communications?

Yes.

We can live without photography.

Excellent design can be realized without photography.

If I have a goal here, it is to resurrect Sontag’s arguments against photography, and to challenge our dedication, devotion and desire for all things photographic… leading to a new ethical framework for design.

In the next Dear Designer, I will try to outline the options and opportunities that exist for us if we choose to abandon, even experimentally, the use of photography.

Meanwhile, thank you for reading. I’m very grateful to have you on this road of recovery and discovery with me as we explore the near term future of design.

And to my photographer friends and colleagues, I say keep shooting. I love you. And no, I’m not buying that Fujifilm X100VI yet.

Yours,

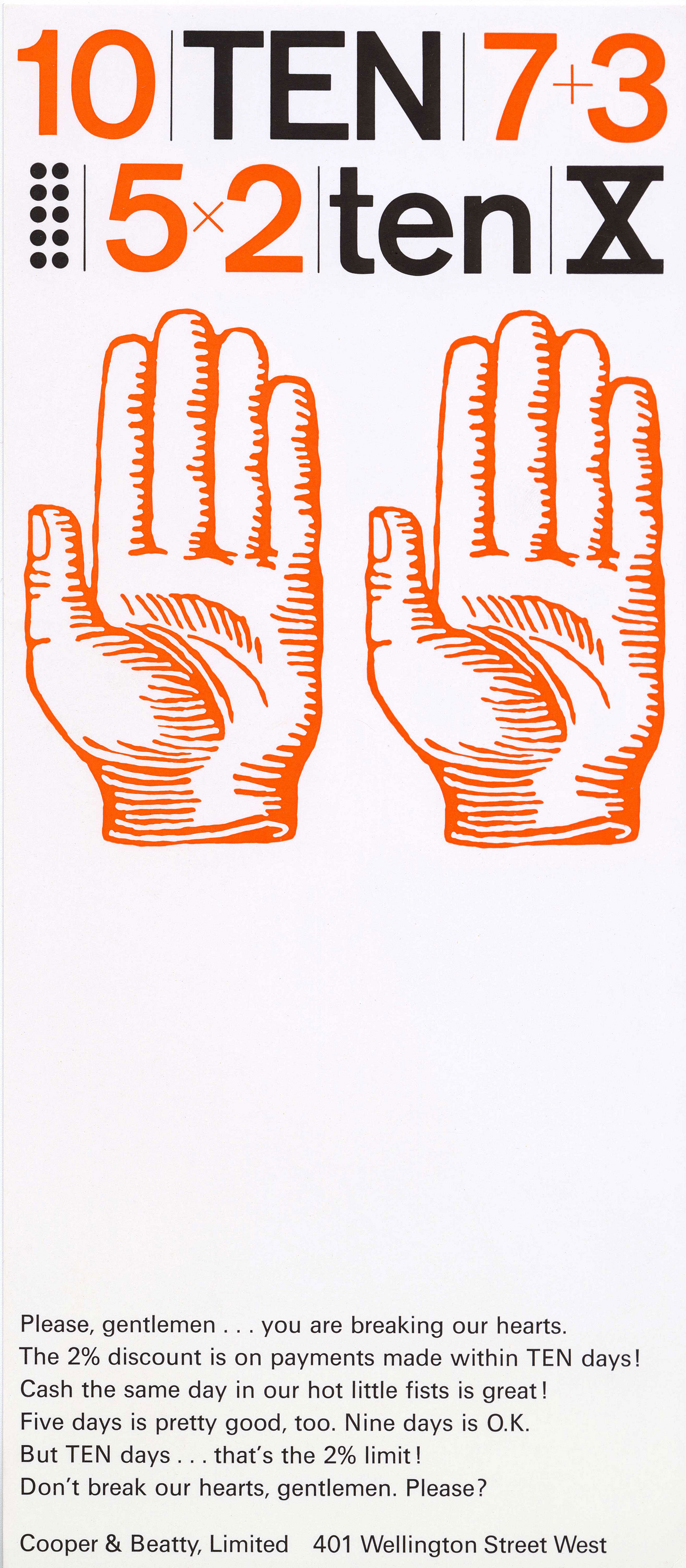

Image of the Week

In 1963, Canadian designer Tony Mann created this little postcard for clients at Cooper & Beatty, an agency in Toronto, to let them know that invoices paid within ten days would receive a 2% discount. The top of the card shows seven different ways to represent the number 10: numerals, text, math, symbols and icons. There are probably a dozen more ways but, set in Standard Medium (Akzidenz Grotesk), the idea comes across perfectly. The bottom of the postcard explains further in more pointed and funny, if gendered, language. I appreciate the negative space, giving the designer power, and us, pause.

Quote of the Week

Cameras define reality in the two ways essential to the workings of an advanced industrial society: as a spectacle (for masses) and as an object of surveillance (for rulers). The production of images also furnishes a ruling ideology. Social change is replaced by a change in images. The freedom to consume a plurality of images and goods is equated with freedom itself. The narrowing of free political choice to free economic consumption requires the unlimited production and consumption of images.

— Susan Sontag, from “On Photography” (1974)

There are nearly 400 subscribers like you on this list. Would you mind sharing this with another designer or artist friend? I am trying to get to 1,000 subscribers. Thank you.

Oh, and if you would like to subscribe now you can do that here, too.

The X100 has a fixed lens, 35mm equivalent, which should stop any lust after new lenses.

As for the 12 points against photographs/photography, I respect your opinion.

I personally choose to avoid any contaminated social entity, that tries to abuse my thoughts with photographs, words, A/V, ... etc. 😊