Designers Don’t Read Books (at Work)

Plus, announcing TypeQuote, a new way to read quotes (wherever)

Dear Designer,

I had an incredible, luxurious and odd studio space for over ten years. We called it the tree house. Built on top of a century-old mechanic’s garage just a few meters behind restaurants and storefronts, I was the first tenant in this custom timber frame building that looked like it could withstand 350 mile an hour winds.

A red steel roof protected us from the elements. Me and five or six designers and developers had desks near a bright, day lit window where we could watch the snow, the rain, the wind and the world.

I had my own private office, a place of quiet refuge that I never felt like I quite deserved. It was weird to be separated from the rest of the team but, as the principal of the studio and its resident sales dude, it was wisely beneficial — I could keep the many private phone calls related to client development, partnerships, money and management private.

Within that little office, I had shelves and shelves of books. Most of them were related to design. Others were about running a B Corporation and a conscious company. Still others were about typography, design history, branding, organizational innovation, self development, and managing in a world contested by commerce. There were hundreds of books.

Do you know how many I read during the daylight hours? Fewer than a dozen. And I can easily count on two hands the number of days that I spent reading those books between my work hours of 8 am to 6 pm.

Let’s do a calculation for a more exacting science. That’s 10 hours per day x 5 days per week x 45 weeks per year x 10 years = 22,500 hours spent at the studio. If I read 10 days, that amounts to less than .01% of my work life with my head in a book.

I love books. I buy books. I’m a measured reader but I read books all of the time. Well, at night or on weekends and lately, in the morning before work.

So, why didn’t I read books during working hours?

(Note: By books, I mean paper books. While many read books on a device or by audio, I’m talking old school, wood pulp pages bound with covers and glue.)

First and foremost, the knowledge industry (adjacent to the culture industry but spiked with invention and ideation instead of entertainment), no longer allows for reading books on company time. That sounds weird, especially since I owned my own studio. But it’s true. Look around your office. Visit a co-working space. Go to any cafe. Unless you’re in a library, the number of people visibly reading a book during the day is near zero.

It’s not that we are not “allowed” to read. We designers read all of the time — on a screen or perhaps on a printed 8.5 x 11” sheet of paper. But, today, we are expected to learn, think and create on the same devices that we use to read. In other words, the activity of modern knowledge acquisition by workers is built around a highly circumscribed culture of media discrimination.

Basically, we are expected to learn on the same tools that we use in order to produce. Our culture valourizes digital as professional pursuit.

What is this about? I suspect it’s about a kind of mutually enforced alignment around productivity. If someone is seen reading a book, it must be for “pleasure”. The person isn’t “working” per se; they are “enjoying themselves”. They are being spirited away. They are “relaxing”. They are not adding to the economic activity of our digital environment — instead, they are taking time for “themselves”.

This is insane. G-d forbid that you are caught reading a book on productivity and efficiency at work.

The second and related reason, we don’t read at work is the acute perception that book reading means time is being wasted. We are no longer allowed to “abuse” or “squander” our own time.

Stoicism is a popular conceptual framework for personal growth and self development these days. Many authors have built a very good living telling us to be stoic and strong, to hold on with quiet determination, to manage our lives with quicksilver and a dash of mercury. Quotes by Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus (respectively) appear in our feeds:

Death hangs over you. While you live, while it is in your power, do good.

How long are you going to wait before you demand the best for yourself?

While there are clear benefits to Stoicism such as living to day as if it’s your last, the internal pressures required to make every hour productive is a conservative feint.

I can tell you that it hurt me. During those ten years of running Manoverboard in that fine, fine studio, I overworked myself, sometimes driving myself into a muddle, or a puddle, depending. I thought: I cannot waste a moment or I will lose out on an opportunity, reduce my social impact or authority, or worse, disappoint my team and our clients.

This is a fool’s bargain. I was the fool.

Reading a hardcover book during the day felt like I was putting me over the machine. So I didn’t do it. The machine, and, I suppose, the economy, won out 99.99% of the time.

The third reason people don’t read during the day relates to attention. There are innumerable (ahem) books, on the attention crisis, starting with Nicholas Carr’s celebrated The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains (2010), which is ruining our capacity to focus, to maintain interest, and to persist in learning. Carr writes of early media theorist Malcolm McLuhan:

What both enthusiast and skeptic miss is what McLuhan saw: that in the long run a medium's content matters less than the medium itself in influencing how we think and act. As our window onto the world, and onto ourselves, a popular medium molds what we see and how we see it—and eventually, if we use it enough, it changes who we are, as individuals and as a society. "The effects of technology do not occur at the level of opinions or concepts," wrote McLuhan. Rather, they alter "patterns of perception steadily and without any resistance." The showman exaggerates to make his point, but the point stands. Media work their magic, or their mischief, on the nervous system itself.

There has been some reevaluation of this theory lately. Historically, every technical innovation since the Renaissance has created untold cries of worry.

Maybe it’s not attention deficit disorders or digital devices that are keeping us from books but the sheer number of activities simultaneously available to us knowledge workers. Maybe there are just too many wonderful ways to spend an hour.

But I know that my attention span is diminished. On a good night, I can read for 30 minutes before falling off. If I’m outdoors, I can read longer — perhaps 1.5 hours; there is usually no fridge, computer, or other pleasurable distractions. If I’m inside, on the couch or chair, I can clock an hour before becoming either bored or bottlenecked.

The attention economy is a real issue that deserves our attention. Corporate monopolies, advertisers, and device manufacturers outpace each other to compete for our 1,000 minutes of awake time. Americans spend about 2.25 hours per day on social media. Canadians spend fewer hours, at around 1.5 per day. But worldwide, these numbers are increasing, thanks to Facebook, TikTok, X, Instagram and Snapchat in that order.

Or maybe not. According to Publishers Weekly, after two years of mild declines, print book sales saw a 1% increase in 2024! More people are buying books, especially adult non-fiction, the exact types of books that designers might be reading during the day (or evening, and night). I’m heading to a design-focused bookstore this week. Maybe see you there, dear designer.

Yours,

Bonus: Announcing TypeQuote

I have always loved a good quote. A great quote is even better. It can challenge your every fibre and inspire our every move.

As a bonus feature for subscribers (I know, there aren’t too many), today I am launching TypeQuote, a project I’ve been thinking about for years: a site that features quotations that I love or that I think are important. Each day, a new quote will appear, automagically. The site will feature quotes, long and short, good and great, about design, typography, books, writing, existence and cats.

In the next issue of Dear Designer, I’ll explain and explore TypeQuote. Stay tuned.

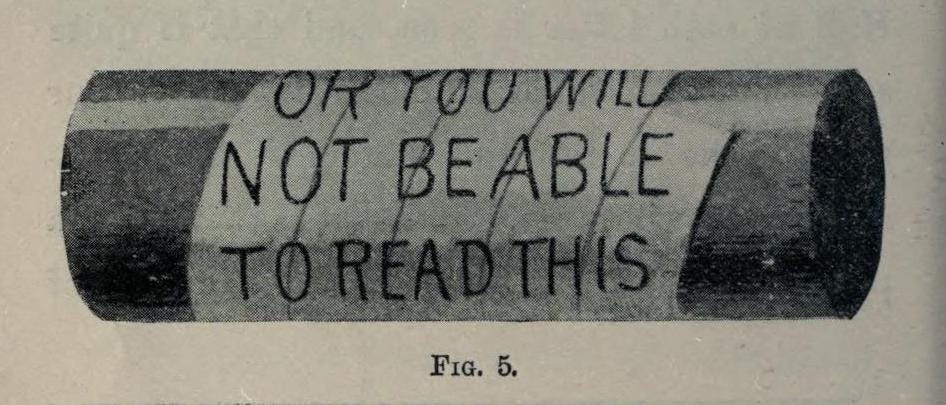

Image of the Week

When I was eight, I came up with a system of secret letters that I could use to communicate with one of my friends. Each letter of the alphabet had an odd and corresponding made-up glyph. I found the cheat sheet a few years ago but I’ll have to dig it up again.

I love the above illustration from a book called Cryptography by Frederick Edward Hulme (1841–1909), an artist and naturalist. Here, Hulme shows a piece of paper that is wrapped around a certain size cylinder that allows the reader to decipher the message. If the cylinder is smaller or larger — or, if the prospective reader doesn’t recognize the feint — all you see are a bunch of lines or half letters.

First mentioned in the 7th century BC, the scytale may have been used for authentication and not critical messages. Perhaps it was too easy to break by those Greeks, who had more time on their hands and fewer screens.

Quote of the week

Rationality is what we do to organize the world, to make it possible to predict. Art is the rehearsal for the inapplicability and failure of that process.

~ Brian Eno

Thank you for reading, dear designer. Would you do me a favour and share this with a designer or artist friend? I would be grateful. I am trying to get to 1,000 subscribers, after which something will happen.

If you want to subscribe you can do that here.

This was great. If I ever start a studio and have employees—which, to be fair, I don't really plan to—I may schedule "reading time" like we're in elementary school.

This idea might end up being why I start one 😂

I remember visiting my dad at work -- when he was closing in on retirement and I was still in college -- and part of his day was reading scientific journals to stay up to date.