Imposter Syndrome Definitively Ends for Everyone at Age 58

On self-doubt, cosmic insignificance, creative survival, and the long arc of becoming

Dear Designer,

For the first time in my life, I don’t feel like a total imposter.

Sure, there is a big f-ing part of me that still feels like I am completely faking it, calling it in, making it up, or putting it out. Part of me feels fraudulent, fricasseed or a flake. Yes, there is that still, strong, simpleton voice in my head that, for forty years, has whispered, “Drew, you don’t know what you’re doing and you sure as hell don’t know what you’re talking about.”

But that voice is a little quieter now, not as strident, not as eager to extinguish my most longed for ideals and hopes and wants. Or, at least, it’s not quite as abominable in volume as it used to be.

First, some questions.

What is imposter syndrome? IS (pardon my diminutization, it helps) is not an actual psychological disorder. But it is a relatively ubiquitous psychic challenge for generally high achieving people that cannot accept their skills or accomplishments in their chosen profession. It is a form of arch self-doubt, an internalized fear that no matter what they do or what they say, they are swindling others because their success is predicated on their powers of deceit rather than their years of hard work, learning and knowledge.

It’s a rotten trick, IS, not unlike how some people (like me) experience insomnia, in which they cannot sleep because they think they cannot fall asleep, so they do not sleep. IS is a trick of the mind in which tricks are overly minded.

People with IS also often suffer from anxiety and depression, have a greater propensity for somatic issues, and it cuts across gender.

Many designers I know suffer from IS. Why?

My non-informed (there we go) theory is two-fold. In a practical way, those who are attracted to creative professions — writers, artists and their ilk — demand a lot of themselves in their delivery and presentation. They may not necessarily be perfectionists, but they know that their work (even the smallest of drawings, the shortest of poems, the simplest of patterns) is to be judged not simply on its own merits but on the totality of their very being. Creative individuals, at least in their early days of discovery and production, will often suffer from the narcissism of their own ideals.

Imposter syndrome gives us, dear designers, asks us to look twice at the act of creating something new in the pantheon of the old. It offers an anxiety of disapproval and disappointment, protecting you from hurt, shame and humiliation. IS keeps you from working because it tells you that the work has already been done, and done better than you.

And, if you are a student of cultural history, you recognize your own lightness in the rich and long chronicle of contributions from those that came before you. As a sufferer of IS, you feel that your small dot on time’s arrow diminishes as each and every day passes.

But I think there is a second, more abstruse reason, that IS gets a command performance from designers and creative folks. Sensitive to the world around us, we are not just competing with millions of others in the pursuit of the original, the new, and the peculiar. We are also competing with the dynamism and glory of nature, of godhead and of our universe. Every day, tiny babies and massive stars are born, the grass grows gross and glassy green, and the rains come tumbling down. We humans are small and still in the mere midst of infinitude, the great unfolding of eons and energies all around us, time turning in tumult.

Our slight voices, in this vast and vertiginous place, are quiet when we sleep and soft when we speak.

We are not actually in competition with nature’s outrageous and overt momentum. But, also, how can we not be? Our every action is fraught and fragile, our love for one another contingent upon another, our creations thin and meagre, with only days or decades away from decay and oblivion.

In this still, sweet presence of our existence, we push new things into the universe, hoping that they will take hold, last a little, stay for some time, all the while, we know they are both wild and wilted.

And yet! We persist. Artists, creators, designers and writers, we make our claims and perform our stunts because we are also aligned with that great unfolding and we know that we ourselves benefit from our musings and our makings.

The alternative is to close up or to close down. I’ve done that. And, let me tell you, the act of inaction is a terrible, frightening and frantic place to be. Imposter syndrome multiplied by creative paralysis is the recipe for panic.

Oh, please, dear designer, do not stop creating.

Next, question! How is it possible that I’m fifty-freaking eight?

My birthday was only a month ago. I remember being in my thirties and looking at my parents and thinking, well, that’s pretty much it. And, whoa, okay, so that’s me now? I don’t feel like in any way, shape or form to be at the end of my career. I have, or I believe I have, years and years to give, to work, to deliver, to shelter, to deliberate and to provide.

Finally, how do you overcome imposter syndrome, ideally before one turns into a senior citizen? (Also, who came up with that term? In other cultures, there are “elders”. In ours, we call those who are wise and wizened “citizens”, as if they are suddenly waiting out their quiescence on a short, green park bench.)

I honestly don’t know, yet, but I am going to work on this. I do know that it can take a while and it can take a village — of friends, family and therapists. Learning to like yourself takes commitment. Being able to take (let alone give) an earnest compliment nowadays is an art form. Creating work without the fear of being called out, cancelled or crucified is increasingly difficult in a time of conservative cultures on both the right and the left.

We, the makers of the art of the everyday, mostly need to be kinder to ourselves. Allow ourselves to enjoy those periods of inactivity when it is time for retreat, even when the retrenchment is lasting. Give ourselves license to run in a different direction when our hair is burning. Learn to listen and to learn and to listen. Create new magic amidst the mire. And to trust that the dark is also our companion in times of tumult and tribulation.

As Nick Cave says, push the sky away.

Yours,

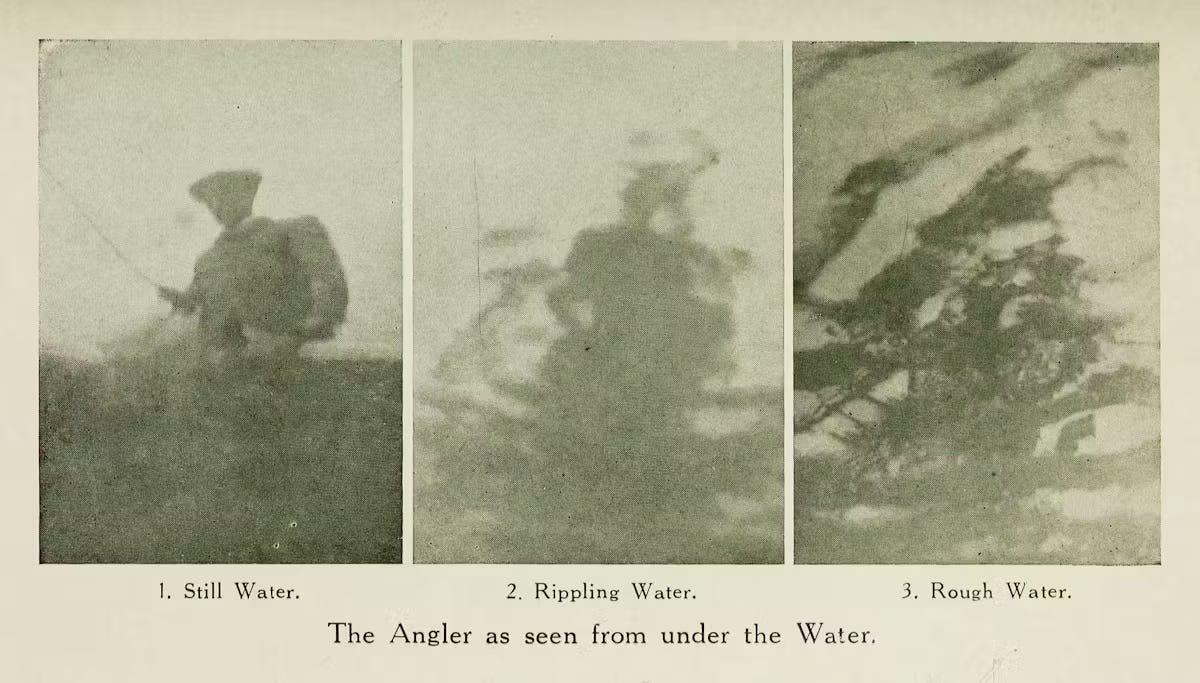

Image of the week

Despite animals (and scientists) being all around us, we truly don’t know what they think, see or feel. In order to catch more and better fish, angler and scientist Francis Ward tried to figure out what a fish would see under water by taking photos beneath a lake. The result is a book of strange and beautiful images that may look exactly like what a fish sees — or do not look anything like what a fish sees. And does it matter? These are anthropomorphic conjectures, visionary and odd, as much Eraserhead as science. All of it bountiful. If you have a chance, scroll through the book for more. Or put your iPhone in a bath and see what comes of it.

Quote of the week

If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.

~ Henry David Thoreau

P.S. Thank you for reading, dear designer. If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can get your very own subscription by clicking the button below.

This newsletter is free and so are you.

It's common in software engineering as well. I worked with a staff engineer who ran a series of lunch workshops on engineering culture. Imposter syndrome was a major topic.

For engineers I think it comes from being so aware of all the stuff you do not possibly have time to learn. The more you know, the more you know you don't know.

For someone who chanced into engineering like me, with no academic background, imposter syndrom is always lurking. It helps to remember that it is so common. We're all otters*, always at odds with the Catholic question of "what constitutes a fish?"

*

Falstaff: What beast? Why an Otter.

Prince: An otter sir John, why an otter?

Falstaff: Why? Shees neither fish nor flesh

IS is an important indicator, if you can separate yourself from it a bit—that might mean that you are continuing to try new things that you aren’t a “pro” at yet!