Living Courageously, At Least This Year

Plus how design portfolios matter in an age of templates, standardization and AI

Dear Designer,

I’ve been following writer, philosopher and podcaster Sam Harris for many years. I’m not always in agreement with his commentary but too often, I am. There is a kind of conservative (with a small “c”) soft logic to his words and, as we progress through this increasingly conservative decade, it’s important for me to review and understand that surly side of the equation.

In his last podcast/newsletter, Harris talks about resolutions — and I actually think “intentions” are better word here — for 2025. He resolves intends to live this year as if it was his last.

Harris notes that he’s healthy and that he does not expect that he will leave this planet in one year. But he suggests that he will live every day, every single day, as if this was it.

Recognizing that this resolution may be easier to do for an established, wealthy, and independent public intellectual than the average, middle-class, working person (e.g. you and I), I’m still going to do my best to emulate it.

In 2025, I’m going to live each day, as best as I can, as if this was it for me.

Why would anyone want to force the concept of existential brevity onto one’s working life?

For one, it quickens the mind. Living as if this year is your last, you can’t help but focus on what is most important to you, on what matters most, on what you enjoy doing and, even more importantly, what you relish in helping those around you.

The idea of living this way has a few nice fringe benefits.

Do I need a list of values or a set of resolutions to accompany this overarching intention? No.

Do I need a system by which to guide my ideas and work over the coming months? Not really. Those are typically overwrought.

Do I need to announce it to everyone? No, but I’m doing it here because, well, Sam Harris did, and because it might be of interest to you, dear designer.

All I need is a list of things I want to accomplish in 2025 that align with the new frame of impermanence. And I need the attention that comes with that frame.

(I might mention that I also used the Year Compass tool this past week to help me look back at 2024 and to help project, direct and manifest what I most want in 2025. The Year Compass is an incredibly powerful tool thanks to its simplicity and probing questions. Many folks have been using it every year and I’d highly recommend giving it a shot. Set aside two to three hours to complete everything. By the way, the touchstone word that I determined would most help me during the coming year: “courage”.)

Dude, where is your portfolio?

One of the “things” to accomplish in 2025 is completing my personal portfolio.

I call myself a designer, a creative director, a sometimes-artist. How come I don’t have an online portfolio? Procrastination. Fear of being judged. Worries about the body of work I’ve created — and not created — over twenty years. Lack of focused time on my own personal projects. Discipline. Technical issues with the site I had built. Disappointment and exhaustion. Illness. Anxiety.

You know — those kinds of things.

I know that I’m not alone in this. But it sure feels lonely when you see other designers, creative directors and artists build and support sublime and substantive portfolios.

…

Over the next few months, my intention is to finish up my portfolio and launch it. Even if it’s half done and half baked, launching it will be energizing. I’m excited about. I designed it nearly two years ago, had it coded, and now just need to finish out more of the content.

But I want to take a moment to jump up a level here. What is a design portfolio and what is going on with them these days?

Twenty years ago, a portfolio was a handmade booklet or a zippered case, consisting of a collection of printed objects. Each page of the book would consist of one printed piece — a brochure, a visual identity, a spread or a series of ads. The work might sit behind a piece of mylar or other plastic. Ot it would be mounted on boards. Viewed together, a potential employer, gallerist or stock reviewer would get a sense of your visual and technical skills and what style, systems, and strategies led you to create what was created.

Designers spent hours and hours sifting through their work, collating it, labeling and organizing it, printing it and reprinting it, refining and refining and refining some more. They would show it to other designers, get their feedback, and refine once again. Portfolios were polished. Designers were resolute in their presentations. For some design associations, your portfolio was your ticket to certification or other recognition.

I know that “crafted” is overdetermined but portfolios were effective because they expressed a personality, exuded professionalism and exhibited polish.

Today, most portfolios are online and the subject matter has not changed much. Portfolios continue to showcase our visual work, process, and outcomes, to the same prospective viewers — employers, gallerists, reviewers, etc. The focus is on digital production — websites and applications and identities plus animation, typefaces, products and campaigns.

But what is different — and what is increasingly upsetting to me — is how poorly most design portfolios appear today. I look at them at all of the time. Whether reviewing unsolicited applications for work, judging design competitions, or actively looking for design collaborators, I’m consistently disappointed in what I see.

What is it that I am seeing?

I’m seeing a lot of poorly crafted portfolios that are hastily put together using a platform that is not right for the designer or the audience. I’m seeing digital work that may look great in Figma or in a browser, but that doesn’t translate to the chosen portfolio layout. I’m seeing portfolios where images are missing or cut off, where links go nowhere, and where contact pages ask you to fill out a form.

I’m also seeing grammatical errors, navigation systems which don’t make sense, and groupings of work that are illogical. I see designers trying to do everything everywhere all at once — present their designs, along with their photography, illustrations, drawings, paintings, animation and process work in inconclusive and incoherent ways. Sometimes, I see the opposite — portfolios that present zero personality — as if the designer wants to appear machined, which in fact, I suppose they might be!

Why is this? Why are design portfolios so fraught these days? I think there are at least three key reasons.

Template design. I am on a Slack channel with a few hundred other designers and a younger designer asked for recommendations in creating their portfolio. The response: Wix! Squarespace! Readymade! Webflow! Yes, those are all fine and dandy options. But if you’re designer, don’t you actually want to design your site? Why hand your heart and soul, your individual agency to another designer who created those templates?

There is a role for template design (upon which the modern web is built) but I don’t understand why a designer would use template for their own portfolio.

Not if one wants to be a designer.

I know the “cobbler’s children have no shoes” line. But we should note that cobblers went out of business 100 years ago.

This is all the more important with the rise of AI and its influence on design. Let’s take the ethical integrity of the portfolio design system itself out of the equation. Would you want to include generative AI images in your portfolio? All of these things are currently converging. To be a designer today means contending with time, energy and financial resources as well as taking seriously the ethical implications of using other people’s work.

UX and standards. There is no doubt that web standards and UX standards have made for a better internet and application experience for the vast majority of people. We need the W3C and the vast code debt to continue building a more ethical and accessible web.

There is an opportunity cost, however, in overly prescribing to standards. Standards, writ large and accepted wholesale, create non-unique solutions that amount to a monotonous and uniform ecosystem. In worst case scenarios, they create mundane and mind-numbing design that can no longer successfully tell a story or differentiate messages.

Yes, designers need constraints. We live best within them. But a constrained soul is a contracted one — and I worry that so many designers are simply filling in forms today. They open up a template and, after massaging content, hit publish. The rise of AI will make standardizing easier and therefore more attractive to some graphic designers. But it will not make for thoughtful solutions and it will not help move the needle when it comes to creating more conscious, human decisions around what is important for us to know.

The feeds are fleecing us. Design portfolios are also in crisis because we are currently in a stage of mass conformity disguised by the permeation of performance. On Instagram and TikTok, individualism is the mantra and yet no one stands out. While this is a democratizing force, it is also a totalizing one, in which we spend our time consuming the “feeds” of big social companies. The human creativity that goes into these presentations (dancing, drawing, designing, etc.) is honest and true; however, the framing device used by social media companies diminutize the creative act in an effort to sell us (and advertised objects) to ourselves.

In the end, we create posts that cannot critique the medium or corporation itself. We design websites that look like everyone else’s. We live in constant fear that the market will move on, which it will. Our portfolios, both in structure and substance, will always feel old, unreadied, archival, even after they see the light of day. We are not abe to rekindle them the way that Instagram can — portfolios are always already static objects that represent a few moments in time.

Why create a great portfolio when my work is on the social network?

Dude, eat your own dogfood

This brings me back to my own portfolio. It’s all well and good for me to critique portfolio-land when I don’t yet have a homestead.

I will. Soon.

More importantly, what I want for designers today — to succeed at all costs, to be unintimidated by AI, to create extraordinary work, to be unafraid of project demands, to collaborate with other designers, and to design consciously and with conscience — is still possible.

Our portfolios are just one representation of who we are as designers. But it’s an important and cogent one.

To your year of good design.

Yours,

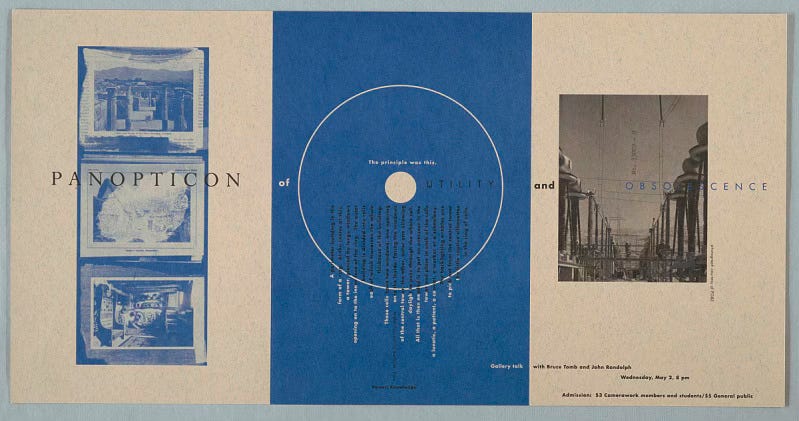

Image of the Week

I am a fan of 1990s print and ephemera, probably because it’s where and how I cut my design teeth. This is a brochure by Lucille Tenazas, a designer who studied at Cranbrook Academy of Art, where she was tutored under the great Katherine McCoy. Tenazas, one of the few recognized designers who are women of colour from that time, made this for an exhibit and series of lectures in 1990 by John Randolph, Bruce Tomb, Lorna Simpson, and Sally Mann. I don’t see this kind of work being made any more. It’s not accessible. It’s un-gridded. It’s printed. It uses only two colours — black and blue on heavy beige paper. The photos are stylistically different and the text is small. And it looks freaking fantastic. (I just so happened to look at Tenazas portfolio. It’s old and only page. But I love it. What else do you need?)

Quote of the Week

[Tenazas] requires her students to use objects of personal significance in order to bring to the fore their ‘personal emotional voice’ as well as using ‘problem-solving and rational thought’.

~ From a 1995 article in Eye Magazine by Teal Triggs

Thank you for reading, dear designer. May the year 2025 bring you custom design.

If Dear Designer has been forwarded to you, golly jeepers, you can get your very own subscription here. Dear Designer is free and so are you.

Oh. If you want to share this with someone, please do, please click:

Riddle me this: The man who is afraid to have his portfolio judged is also deemed worthy by colleagues to judge design competitions.

Just read a fascinating article on the AI impact on developers which I think has a lot of application to designers (https://addyo.substack.com/p/the-70-problem-hard-truths-about). It's what the author calls "The Lost Art of Polish":

It's becoming a pattern: Teams use AI to rapidly build impressive demos. The happy path works beautifully. Investors and social networks are wowed. But when real users start clicking around? That's when things fall apart....

* Error messages that make no sense to normal users

* Edge cases that crash the application

* Confusing UI states that never got cleaned up

* Accessibility completely overlooked

* Performance issues on slower devices

These aren't just P2 bugs - they're the difference between software people tolerate and software people love.