Ragpicking as Professional Pursuit

And why reclaiming intuition in graphic design is a fearsome act of faith

When I was about eight years old, a friend and I were out riding our bikes in our quiet, working middle-class class neighbourhood in suburban Philadelphia. We came across a bunch of striped, blue and white rags lying on the sidewalk. The various fabric scraps were strung together by some light twine and there were probably 20 or so pieces total, all of equal size.

We brought the bunch of rags back to my house and I had the brilliant idea of selling them to our neighbours.

My mom thought I was nuts, but it was the 70s and I was one of those latchkey kids that came and went pretty much as I pleased.

(Those banana seat bikes with streamers on the handlebars that you might see in Stranger Things in the early 80s? Those were no less strange than the purple paisley jumpsuits that both girls and boys wore back then.)

So, my friend and I went door to door on our block. Selling those clean but discarded rags.

Most of the people who we faced, with our small hands in our small pockets, simply said no thank you — and we were the recipient of not a few doors simply shut in our bright faces.

But there was one kind lady a few doors down who said she would buy five rags from us. I over-explained to the homeowner that she could use the rags for cleaning or she could put them together and even sew something out of them!

A ragpicker was born.

I remember thinking, “Wow, this is great. You find stuff and then sell them to other people and then you have gum money.”

Thanks to the sweet, sweet kindness (and indulgence) of strangers, I think we made about $1.00, until we gave up the entire enterprise — probably to watch The Brady Bunch.

Honestly, I thought that I was doing our neighbours a solid — selling folks a bunch of decent looking rags that they could use for their own household purposes.

And yes, perhaps there was a tinge of guilt in my heart as well. Or maybe that’s part of this reminiscence.

But you know what?

I’m still a ragpicker. And in that moment of human exchange, a designer was born, too.

To this day, I continue to love finding things — ideas, objects, people and places — and I am still infatuated with stringing things together and making something new from them. Sometimes, it’s a small business, matching people with design, like I did for so many years with my previous studio Manoverboard.

Sometimes, it’s a website, pushing pixels and prose across the digital transom. It could be a bunch of photographs that I like or a few words that I turn into a poem. Or a newsletter.

I still enjoy going to “vintage” stores, looking for previously appreciated clothing or weird tchotchkes. I collect ephemera, especially American and European brochures and magazines from the 1930s. I have buttons and pens from years ago in a drawer.

Picking Rags and Punching Up

Ragpicking is what designers do. It’s about finding junk and turning it into gold.

Being a ragpicker does not mean you go about your work willy nilly. You need to know where to look, you need to be able to read the signs, and you need to tell the difference between raw garbage and real goods. You need to be on the prowl, looking ahead but thinking behind.

As a creative director at Mangrove Web, the agency that acquired my studio last year, I move through my work picking up idea objects: visual and written, historical and contemporary. Typographic research, examining new visual models, reviewing peers’ and partners’ work, revisiting older mechanisms to create digital products — from the outside, these various tasks may look like junking; but, strung together, they amount to supporting a design process that helps our clients create communications and impact in the social sector.

Of course, today, much of knowledge work is like this — scrapbooking ideas across disciplines and practices. Accountants, lawyers and physicians need to look beyond their solitary perches in order to stay in tune with their respective professions.

But I would argue that modern design is the pursuit of a much more perennial and particular kind of ground research, going forward to go backward, looking down, picking things up, only to go forward again, and again. We designers need to look across disciplines and practices in order to stay relevant and real, including the subject matter of our clientele.

Curating and Creating

The word “curate” comes to mind here. The term became popular ten years ago when Pinterest and other social media platforms allowed you to collect pictures online, grouping and growing them. It could be collection of 1960s housewares or a group of brightly coloured yellow books.

But curation is what you do when you’re looking for specific pre-conceived connections, for making concrete numerous things that are related. Curating is the act of presenting a hardwired collection of idea objects, to present known material in a particular manner that is specific and relatively logical.

For designers, artists and writers, ragpicking feels more honest, more genuine. We don’t know what will and won’t be useful, valuable, or even appreciated. We rely upon intuition and our rag investments to date.

What we do know is that all of it — everything — is potentially magnificent. The world is replete with possibility.

And the act of creation — collecting to connect — is a fearsome act of faith.

This is something that the AI cannot do as of yet, though we know that machine learning, too, is a ragpicker of fierce proportions.

Generally, Designers Are Generalists

It’s become a commonplace that one needs at least 10,000 hours to become skilled in any one endeavour. Whether it’s playing piano or performing brain surgery, we rely upon and trust experts in their fields who have studied, practiced, examined and refined their work over years to study.

In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell popularized the science behind needing 10,000 hours to specialize (though the rule has been partly debunked, including by Gladwell himself.)

And people adore specialists — especially those that entertain: musicians, actors and athletes.

But let’s face it — most of us designers are not specialists. We are inveterate generalists.

Generalism is often used in philosophical circles to describe how we privilege intuitions in creating theoretical principles. It also describes what we designers — née artists — generally do each day.

David Epstein’s recent book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World Paperback makes the case that generalists are actually more important than ever in this shape-shifting world. Generalists juggle numerous interests, creating pathways and patterns that sometimes only make sense later — sometimes much later.

So, an admission. I’m a generalist. A ragpicker. A scavenger. These are not particularly flattering terms today. But by embracing them, may we have a chance to reclaim our self-worth, dear designer, as well as our value to a wary and worried world.

Yours,

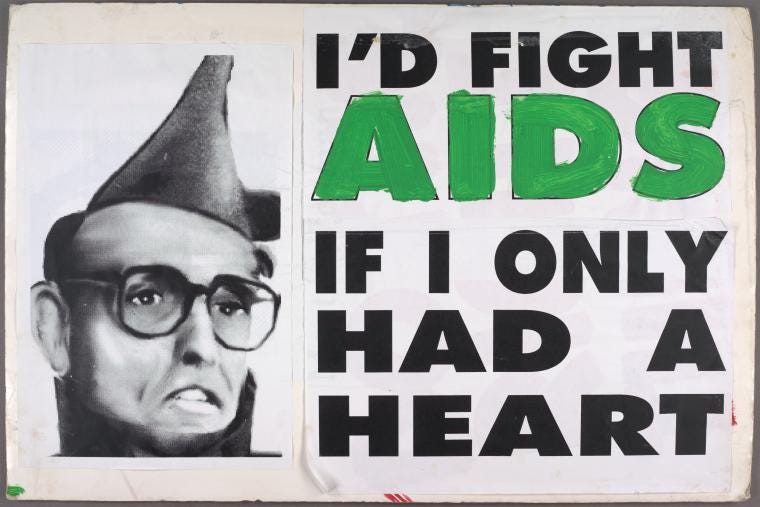

Image of the Week

In the the late 1980s, a grassroots organization called AIDS Coalition to Unlease Power (ACT UP) emerged in New York and around the globe to humanize the AIDS pandemic and to raise funds for research, treatment, advocacy for people suffering from the disease. ACTUP posters were everywhere in major cities and they had the guts to call out public officials like Rudolph Giuliani, George Bush Jr., and Bill Clinton — as well as the Catholic Church. Their visual approach was clever, fresh, and low-fi, using pasteup and photocopying to present an angry and urgent message. Check out more of their work at New York Public Library’s impressive archive.

Quote of the Week

I'm touched by the idea that when we do things that are useful and helpful —collecting these shards of spirituality — that we may be helping to bring about a healing.

~Actor Leonard Nimoy, discussing faith and fortitude in Trying to Capture the Invisible

If this email has been forwarded to you, by jones, you can get your very own subscription right here and now. Thank you.

What a wonderful, whimsical depiction of what it is to be a designer. My heart skipped a bit reading this line: "To this day, I continue to love finding things — ideas, objects, people and places — and I am still infatuated with stringing things together and making something new from them."