Warning: This Design Job May Contain Traces of Human Emotions

Side Effects May Include Conjecture, Vulnerability, and Periodic Self-Doubt

Dear Designer:

Let’s just put it out there. Being a graphic designer today is incredibly difficult. More than difficult than ever, I would argue.

Creating the art of the every day requires consistently engaging with numerous objective and technical realities while also simultaneously summoning real inner resolve and tapping one’s own personal desire to make something unique and meaningful.

Those objective and technical realities are discussed all of the time — there are endless books and blogs and coursework on the subject. They include the means and ends of digital production: tools, systems, approaches, methodologies, resources, analytics and all manner of sets of best practices. Most of these are related to recent advances in technology, user experience and the platforms (Figma, Midjourney, Squarespace, etc.) that we use daily in our work.

We need to know all of this stuff. And much of it is interesting.

But the latter — injecting one’s own personal, material and emotional weight into a visual project — is not discussed at all. Books and blogs and coursework don’t look at these less tangible but equally important aspects of graphic design: feelings, apprehensions, suppositions, guesswork, presumptions, impulses, anxieties and predilections. And can I add arousal and self-indulgence?

We are emotional beings after all and our work often is more psychically demanding than it is technically.

Design is a toolbox

Why? Why are the more human and messy aspects of what goes into our work ignored, elided, or brushed under the dirty beige rug of what amounts to professional development in design? Why do we so readily discuss tools and tech but not tears and fears?

I think it stems from two factors. One is more technological. The other is historical.

First, design today is firmly rooted in the technocratic and commercialized relationship we have developed with everyday things. Design has grown up for, by and with consumerism and it directly and indirectly supports our Megacorp market economy.

Design greases the wheels of mass consumption. See something on social and the internet obliges. Hear something new and ownership is a click away. (One morning last week, I was thinking about buying those fancy new AirPods Max, though these two words really make no sense together. Apple’s website indicates they could be sitting on my bald head two hours from now. I didn’t buy them.)

The technologies that support all our multi-platform communications have instrumentalized design — and to some extent, us designers. Let’s be honest — we have done a bang-up job of supporting our economic infrastructure of wish fulfilment and its parent, consumer capitalism.

Designers didn’t invent capitalism but we do a great job lubricating it.

Consumer infrastructure is rational, built by clicks and content to fuel massive economic engines. Designers, like accountants and engineers, use a variety of empirically drive, socially mandated tools and technologies to service, satisfy and support our economy.

It makes financial sense to talk about and foster design as a toolbox. The practical side of design is well managed and explored. Want to create a dreamy custom mesh gradient across a set of black and white photographs for your own personal brand kit in Canva? Done.

But the emotional and humanistic side of design? That doesn’t compute.

And designers are not the tools

The second reason we don’t discuss design as an emotional, spiritual or psychological practice may be more historical in nature.

Designers were not always designers. Until fairly recently, designers were primarily artists, something that the “industry” of design may want us to simply forget.

In fact, “graphic design” as a term is only 100 years old. In 1922, W.A. Dwiggins, a master calligrapher, illustrator, and typographer, coined the term “graphic design”.

Before this, what we did was called “commercial art”. And we were “commercial artists”.

When I would teach design history, I loved emphasizing this part to students. Designers were, and still are, artists.

My point is that I’m not sure that Dwiggins, whose work happens to be truly gorgeous, did us designers any favours. We lost the “commercial” (which is insincere) but we also lost “artist” (which is a falsehood).

Here is fantastic nugget from design historian Steven Heller:

The people who made roughs, comps or sketches were soon pulled from the press room and placed into the board room, where they worked at a drafting board. It was then, around the turn of the century, that the design profession began to slowly emerge from the primordial ooze. The layout people were unofficially called “boardmen” (mostly men but some women, too). The operative word around the 1890s, however, was “commercial artist.” During this time, “art” was the term for any kind of pictorial material used in printing. It wasn’t a value judgment, but a fact: “Let’s get some art to fill the page.”

(Okay, this took my breath away for a second. I always knew I was a Boardman but I didn’t know I was also a boardman!)

But more importantly, this shows us that we have forgotten that we designers are artists in modern guise. We have the privilege and responsibility of creating art that others get to see, use and enjoy every day. We do that in real time. For the most part, we don’t take this role lightly.

But I would argue that we designers are taken lightly. The emotional labor that goes into creating our artwork, the complexity of managing client feelings and predispositions, the guessing game that comes with invention, the insecurity of knowing when to stop on any given project, the feeling of always being behind in our work and our professional development, the desire to push our own personal boundaries, the range of subject matter that needs to be imbibed in order to deliver, and the worry that we’re doing it all wrong half of the time — all of these go unexplored and undiscussed and unrecognized.

The commercial part of design has been made easy for us. We swim in this stuff.

The artist part not so much. We sit in this stuff.

I’ll explore more about design and emotion soon. Wishing you a good week ahead.

Yours,

Andrew

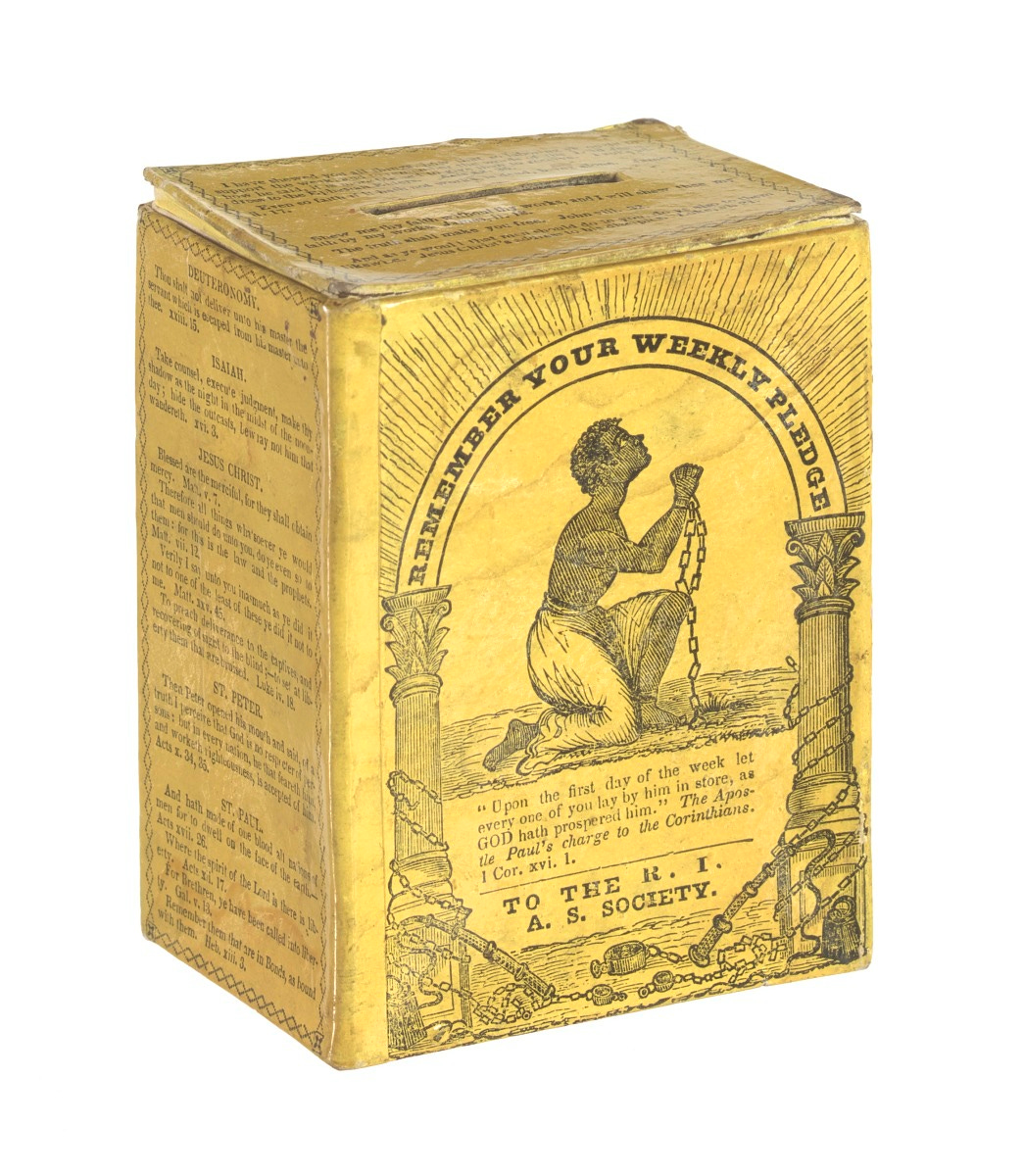

Image of the Week

Every element of this yellow box is designed to support its role: to collect money for the abolition of slavery in mid-nineteenth century United States. From the engraving of the freed slave to the arch of rays of light and the numerous phrases from the new and old testaments (ISAIAH. Take counsel, execute judgment, make this shadow as the night in the midst of the noon-day; hide the outcasts, bewray not him that wandereth. xvi. 3), to the yellow cardboard itself, this box is meant to inspire and compel weekly pledges of money and remembrance in northern households.

Quote of the Week

If you don't get your type warm it will be no use at all for setting down warm human ideas... By jickity, I'd like to make a type that fitted 1935 all right enough, but I'd like to make it warm — so fll of blood and personality that it would jump at you.

~William Addison Dwiggins

If you’ve been forwarded this email, by jickity, you can get your very own sub right here. See you soon.

This issue is da bomb. From specifics like vocabulary (elided - love that word) to simile (like a dirty beige rug) to your realization of being a "board man" and all within the context of what it means to be an artist. Keep writing!

Did this ever hit home. My mind is still circling around it.